Honored figure of culture and arts of Ukraine

The author of monuments to Mykhailo Bulgakov and Les Kurbas, as well as memorial plaques to Boris Pasternak and Serhii Paradzhanov.

Why is it worth reading?

Agree, it’s hard to imagine the modern Andrivsky Uzviz without a monument to Mikhail Bulgakov. It was Mykola Rapai who made sure that Kyiv was the first to crown an outstanding writer with glory.

Mykolay Rapai is not only an iconic sculptor, but also a genius of friendship. He was friends with Georgy Yakutovych, Oleg Antonov and Serhii Paradzhanov for many years. At the time of recording the interview, Mykola Pavlovich is 90 years old, and believe me, this is by no means an obstacle to pleasantly surprise you

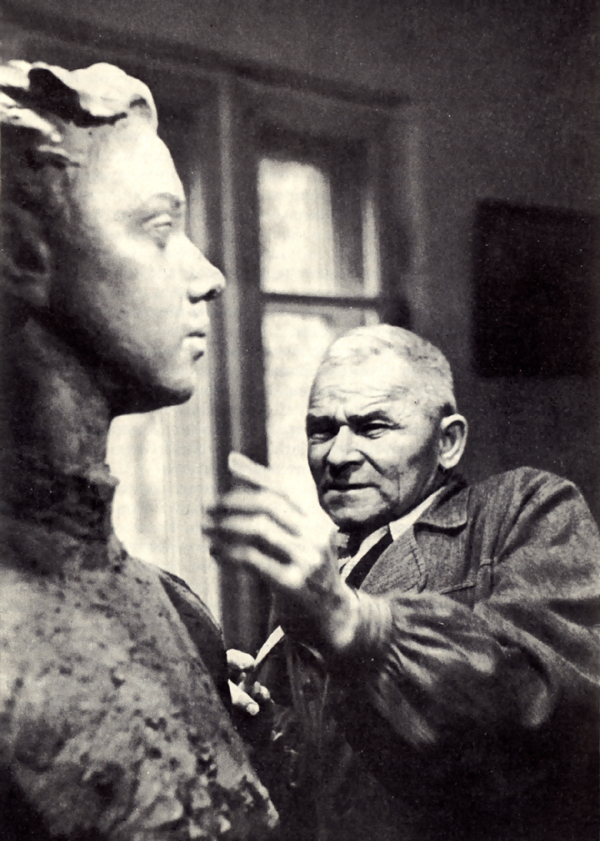

About sculpting

Life must be present in my sculpture, moreover, awe for life must be visible.

By doing sculpture, I wanted to understand a person, to understand who he is. While working on portraits, I noticed that a person’s face changes in every possible way during the work process. When he sits down to pose, he is alone, after a while he becomes someone else, and when he comes tomorrow, he is already someone else. Based on this, I wanted to understand what he is like? What is its true manifestation, what is most characteristic of it and what is most important to it.

For myself, I outlined that life should be present in my sculpture, moreover, awe for life should be visible. Such things are achieved intuitively. There is a bit of mystery in this work.

Childhood

— Nikolai Pavlovich, tell us, what family were you born into?

— My parents are the simplest people among the people: my father is a farm laborer, my mother is a hired help. Dad is from near Poltava, and mom is from Kuban. The father left home because they had a huge family, but there was nothing to eat. In search of work, he reached Kuban, where he met his mother.

The year was 1917, the civil war was in full swing. My father served in the cavalry in the Kuban. After the war, my parents settled on the Rodniki farm, built a hut and lived there until their death. These were Ukrainian settlements; since the times of the Zaporozhye Sich, the mentality in these parts was Ukrainian. The first settlers in those places were Cossacks, who were resettled there by Catherine.

— Did your family support Soviet power?

— I grew up in a family where the Soviet regime was treated very poorly. I still remember how my dad openly denounced the Soviet regime and Stalin personally. I asked my father why he talks about things that are forbidden, because one day such conversations can be heard and reported where they should be. He didn’t really listen to my warnings and, in spite of everything, continued to terribly curse the Soviet regime. The fact is that he was one of the dispossessed.

Even when dad was dying, he was glad that he managed to survive Stalin. I remember how he then said: “Thank God, I survived this mustachioed bastard.”

When dad was dying, he was glad that he managed to survive Stalin

According to various estimates, up to 3,000 people died in the crowd at Stalin’s funeral.

— How did you perceive your father’s harsh judgments?

— Like everyone else, I went to a Soviet school, where there was a completely different spirit. In Soviet times, all schoolchildren were forced to belong to the Komsomol, and I could not evade this either. The things I heard at home and at school caused me internal conflicts. However, over time, I learned to somehow process them and not get into trouble.

— What was your childhood like?

— I had an ordinary rural childhood. When I went to school, we worked on the collective farm in the summer and studied in the winter. At the same time, my friend and I started drawing. After the 8th grade he entered the Odessa Art School. I also wanted to enroll, but my parents didn’t let me.

When Dimka returned for the winter holidays and talked about his studies and life in Odessa, I was dying of envy for him, I wanted to study so much. In the summer, when I could enroll again, I began to persuade my mom and dad to let me go. At that time I had already finished 9th grade.

However, parental consent was not the only obstacle. Today this will probably sound crazy, but then we didn’t have passports, we lived like serfs. Therefore, I took a certificate from the regional center stating that I really live on the farm – and with this certificate I went to apply.

We didn’t have passports, we lived like serfs

— Was it easy for you to get admitted?

— When I arrived in Odessa, the exams were already over. It took me half a month to get there, and that’s why I was late for the exams. It was just the first years after the war, it was 1946, and most of the trains were transporting all kinds of military cargo. All the passenger trains were packed with people, and it was impossible to get anywhere. Besides, I didn’t have a ticket, and when the ticket inspector walked by, the women hid me under the bag racks.

Although the entrance exams were already over, I managed to get in because there was a shortage of sculptors. It so happened that at the admissions office I accidentally met the director of the school. When I told him that I had come to enroll, he asked where I was during the entrance exams. In response, I told him how I changed from one train to another, how I got there by freight trains.

When the director asked what I would like to study, I replied that I had come to study as an artist. He said that an artist is a loose concept but asked the secretary to check the lists. After looking at the lists, the secretary said that it was too much for the picturesque one. Moreover, there is already a whole queue in case someone drops out.

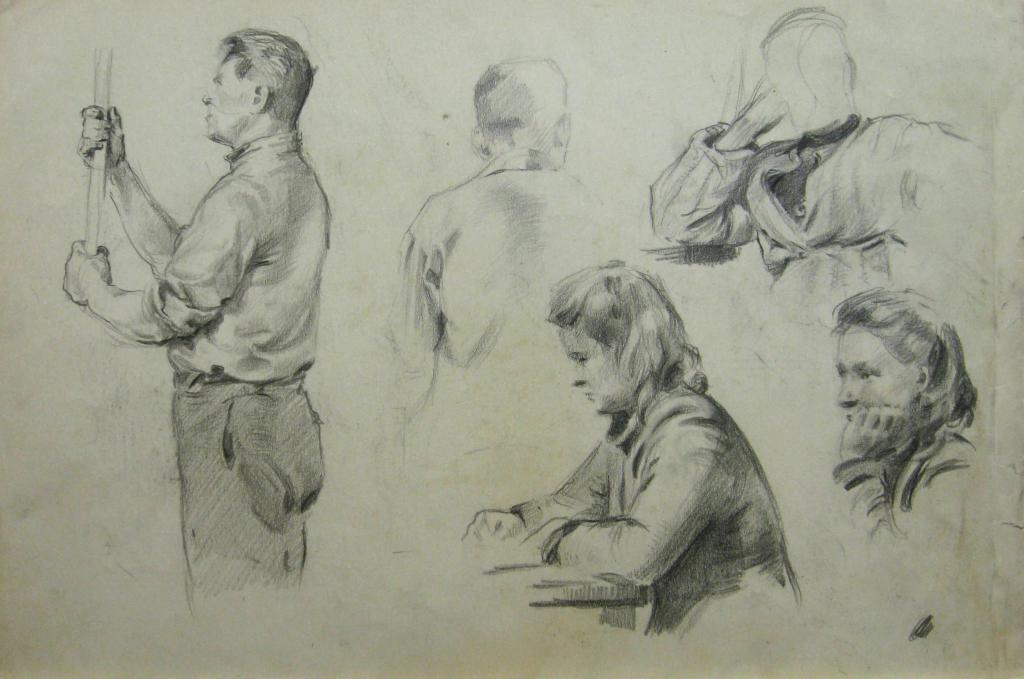

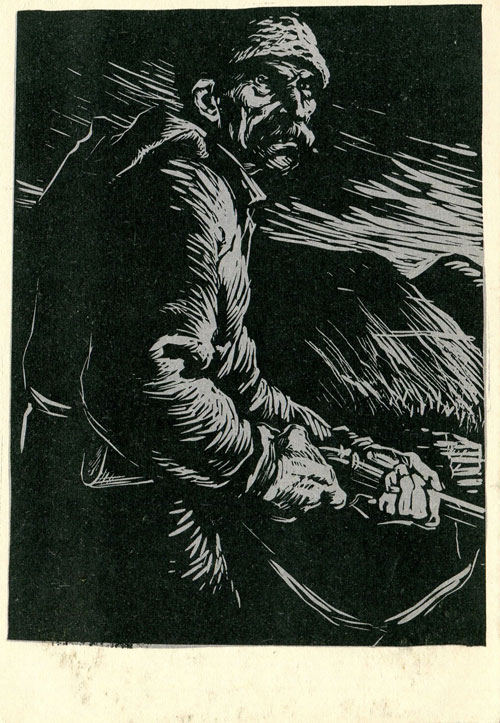

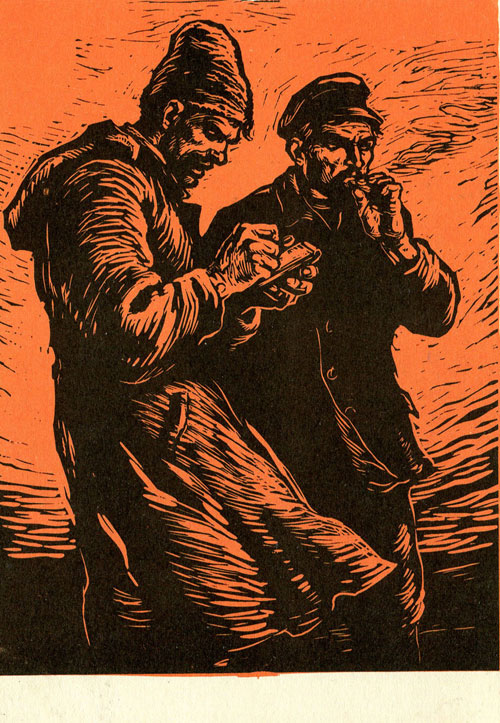

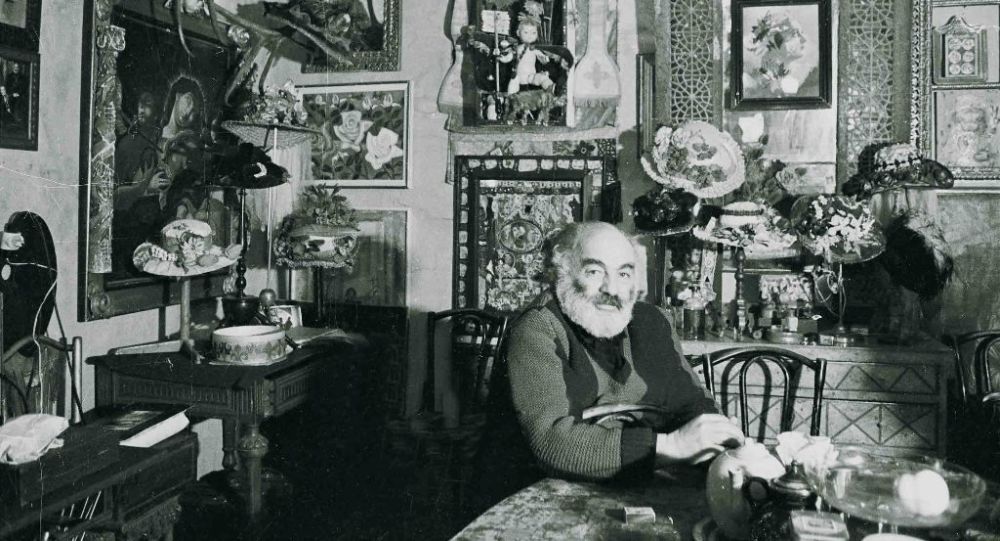

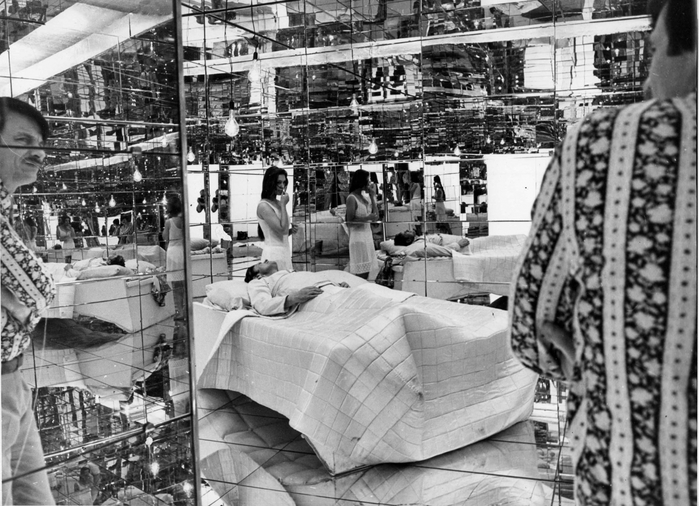

Teachers and students of the Odessa Art School

— In the end, did you manage to enroll?

— After listening to me, he said that instead of art, I could be enrolled in sculpture. I say: I want to, enroll. Having agreed to the sculpture, I did not know what it was. It was important for me to stay in school, and I grabbed this opportunity. I couldn’t imagine returning home with nothing.

Of course, as soon as I arrived in Odessa, I wanted to paint. Back on the farm I drew pictures on plywood, depicting the night or the moon. What I drew then was completely primitive, but I really liked to draw, and I did it with pleasure.

Once at the school, I did not regret that I entered sculpture. It seems that fate itself brought me down this path.

I couldn’t imagine returning home with nothing.

Education

— What was your training like?

— The Odessa School had a very high level of teaching. Before the war, it was not a school, but an institute, and with good personnel. Painting, sculpture and drawing were taught by professors. In fact, we studied like in college. When I studied at the institute in Kyiv, I did not have a school like in Odessa.

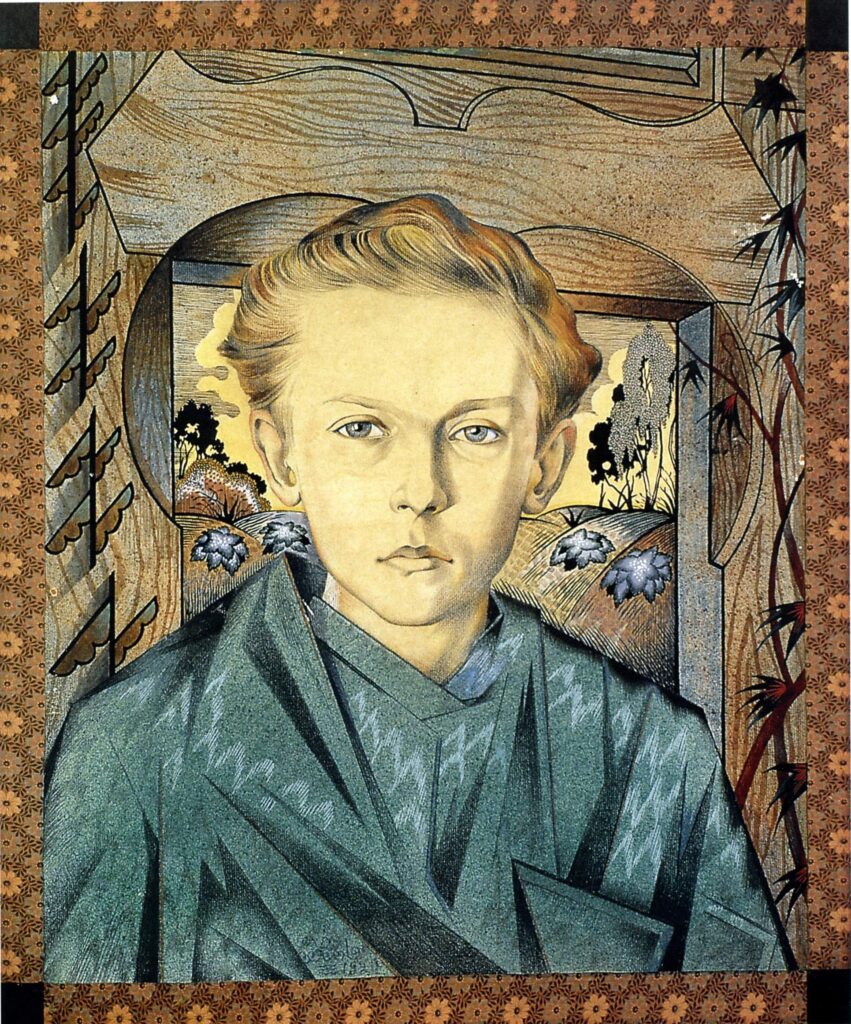

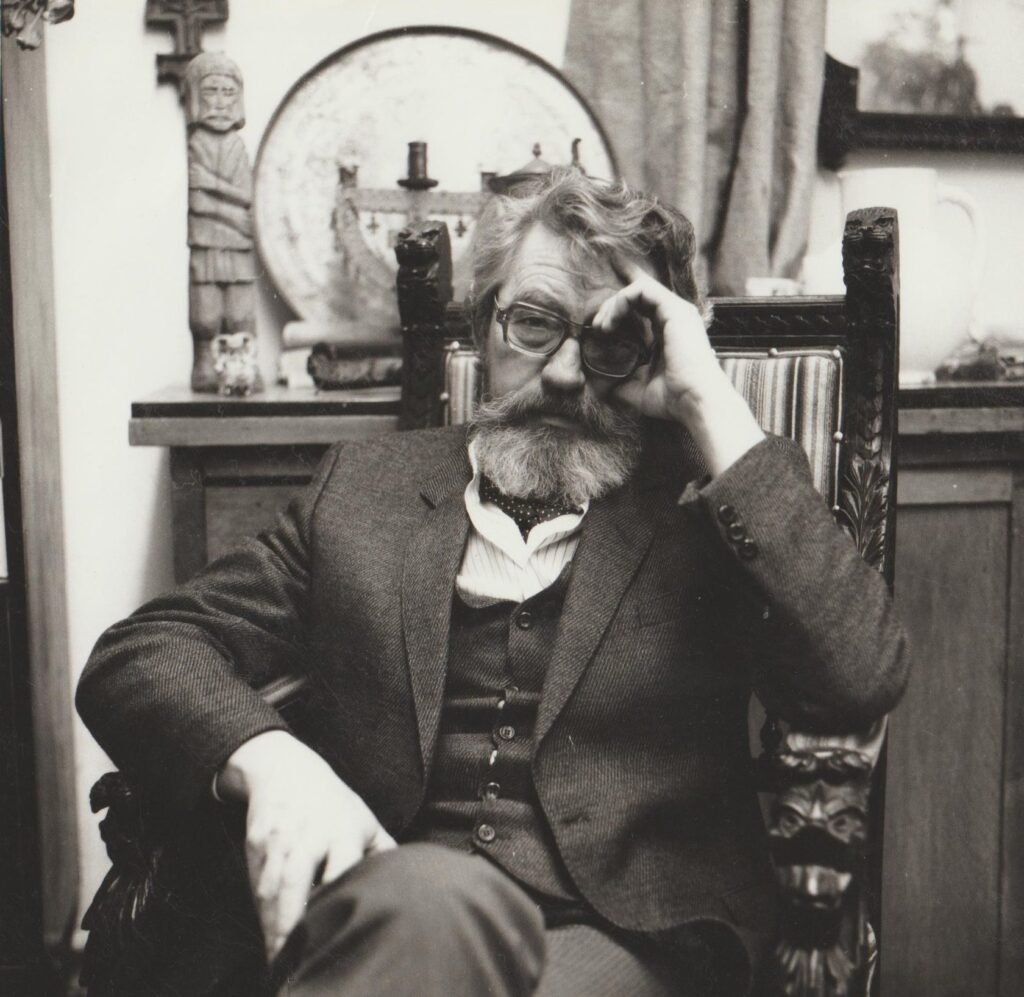

Teachers of the Odesa Art School: from the left, Mykhailo Zhuk, from the right, Teofil Fryerman

— Can you tell us more about your teachers at the school?

— Mikhail Ivanovich Zhuk was very memorable; before the war he was a famous avant-garde artist. In those days, artists of his style were called formalists and were persecuted in every possible way. If you take the same Boychukists, they were expelled and shot. At the same time, he somehow survived and taught with us. He somehow managed to settle down quietly, so that no one would bother him.

When I lived in Kyiv, I specifically went to the library to look at his reproductions in the magazine “Nova Generation”, which was published in 1936-37. After seeing the reproductions, I realized that he was a great artist, his work was amazing.

We were also taught painting by a first-class master, Theophil Fraerman. Our sculpture was led by a young sculptor who had just graduated from the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts and was assigned to Odessa. We had a very good school, the Odessa school was very authoritative.

The works of Teofil Fryerman and Mykhailo Zhuk

— What were your studies and life like in Odessa?

— It was a terrible year then: 1946-47 we were actually starving. A piece of bread was given on a card for two days. The scholarship was small; it could not be used to buy anything. We were starving, but we worked and studied mercilessly. Literally obsessed. I was in some kind of euphoria, understanding what art is, what music and ballet are. I went to concerts and lectures on music. He often visited the theater or went to the opera. The process of understanding art took place in Odessa; I eagerly tried to assimilate all its aspects. I immediately ran to where something was happening: I was interested.

We starved, but we studied and worked obsessively, mercilessly.

— Tell us about entering the Kiev Art Institute?

— There was quite a big competition: 60 people for 9 places. Of course, later there were more competitions, but in 1951 this competition seemed quite serious to me.

I got into the art institute second because when I wrote a dictation in Ukrainian, I made about 80 mistakes. I copied it from my neighbor and made 80 mistakes. Since I got all A’s, the teacher was asked to correct my mistakes a little – and she gave me a C.

— What was the training like in Kyiv: was it better or worse than in Odessa?

— Until the third year, no one could teach me anything. In general, their teaching methods gave me a strange feeling. What they demanded seemed strange to me; I understood everything differently.

In my third year, drawing was taught to me by Alexander Ivanovich Syrotenko, he was from the Boychukists. He, like Mikhail Ivanovich Zhuk, who taught me in Odessa, somehow became a teacher – and thereby saved himself. Alexander Ivanovich gave me a lot and also supported me.

He understood that I understood him, and I understood that he, in turn, understood me. For me, such things have always been very valuable.

— Can you remember some incident related to Alexander Ivanovich?

— When I started drawing nudes in one of my first classes, he came up to look. When he arrived, I only had time to apply the first lines. In several strokes I drew one line after another. Make so-called visits. In these approaches, the shape was not along the contour, but went beyond the contour. This approach demonstrated a level of understanding.

Seeing the drawing, Alexander Ivanovich asked: where did you study? I say: I studied in Odessa. He says: the way you outlined your hands is a competent understanding. At the same time, he told me that if I support the edges of the mold a little at a time, it will curl.

— What happened in the fourth year?

— If the first three courses were general, that is, they taught sculpture and drawing, then in the 4th-6th course we went to the workshop of the professor, who guided us to the diploma. This professorship included Lomsky, Lysenko, Oleynik and Max Isaevich Gelman.

— So that you could remember Lysenko?

— First of all, Lysenko was a creative person, he fantasized a lot and eventually composed many good compositions. He had many sketches, but most of them were never brought to life. On the part of the Soviet government, he was destined to make official orders. For example, he drew sketches for monuments to Lenin and Shchors.

Lysenko was very infectious; using his sketches as an example, he showed us how he felt about sculpture. He had very good sculptures, I saw them in his studio. Moreover, I believe that he is a very valuable sculptor for the history of Ukrainian sculpture.

“My best work is my students”

— After graduating from the academy, did your relationship remain as warm?

— After graduating from the institute, Lysenko invited me to work in his workshop as his favorite student. Then I already knew what it meant to go to work in a workshop. In essence, this meant carrying out his own orders instead. In other words, it was real slavery. I thanked him but declined.

It was such a thing that in fact the professors had their own slaves from among the students. They paid the students a few pennies, receiving a lot of money for the work done.

After this, Mikhail Grigorievich harbored a grudge against me. Actually, when I started taking part in exhibitions, he harshly criticized my work. Of course, I knew why he was doing this; no one but myself could understand it.

—What did you oppose to his approach?

— Everyone around me was engaged in making independent creative things and then exhibiting them at exhibitions. Consequently, the works were bought directly from the exhibition. The income received in this way was quite enough to work for pleasure, do something creative and at the same time hold out until the next exhibition.

Circle of Yakutovych

— How did you meet the Yakutovich family?

— I met the Yakutovichs by chance at the institute. I would say as things go. Although they were somewhat older than me, we literally became friends immediately. After graduation, they invited my wife and me to live with them, and we agreed. We lived together as one family for two years.

— Can you tell us more about how you lived in one house, one family?

— We had our own hobbies and fantasies. We had just read the novel by the Italian writer “Via del Corno”, which translates as “street of poor lovers”. After reading, we were inspired and organized an imaginary republic in honor of the name of the Kudryavskaya street on which we lived. Thus, we had our own Kudryavskaya Republic.

The Republic was the place where we were free, no matter what was happening outside. In this place we completely ignored the official ideology, instead we lived our dreams and our understanding. We argued and looked for new ways to make our art more expressive – that’s what we lived for.

And then, after the republic, the leaven was laid in us. And then we went on our way, each of us met periodically and gathered for festivities. Then we lived every day. In the same house, in the same apartment. That’s why there was a republic.

The Republic was the place where we were free, no matter what was happening outside.

— Tell me more. For example, did you have your own government? And what did its meetings actually look like?

— We had all the roles and portfolios distributed. Yura (Georgy) Yakutovich was the president, Asya (Alexandra) was the president’s lady. Sasha Gubarev was the Minister of State Security, and I was the Minister of War. Grisha Gavrilenko was our Minister of Culture, and Sasha Danchenko was the Minister without Portfolio, that is, the Minister for Special Assignments.

We had our own headquarters and honorary titles. Cabinet meetings were combined with feasts, accompanied by drinks and songs. Instead of a toast, everyone reported on what they had done recently, and then we drank together for this matter. In general, it was a game, but it was all very nice to us.

— Tell us more about Georgy Yakutovich?

“In our circle, in our republic, he was a leader, a recognized authority. Yura was a well-read, widely educated person. We had great respect for his art. By that time he had made a cool relief of the Fata Morgana. With this relief he was nominated for the Stalin Prize, but fate did not. In any case, this work was heard throughout the USSR.

At that time, Yura was already a recognized highly professional Ukrainian artist. By the way, it was also celebrated in Moscow. We grouped around him as if around a leader. Yura’s opinion was very important for us, not absolute, but important. You need to understand that we had a lot of disputes.

Then Yura Yakutovich came to my workshop when we were already old men. We met like brothers, there was incredible warmth between us. I remember now, and there are tears in my eyes.

— Was it only Yakutovich who was authoritative, or perhaps someone else?

— Grisha Gavrilenko enjoyed high authority among us, and Yura Yakutovich too. Grisha had an original taste, in general he is a person of very high taste. His stylistic and visual explorations in graphics, engraving and drawing were very important for art.

Grisha studied China and introduced us to it. I discovered Morandi and became fascinated by the parameters of his works, in particular the square stroke. Inspired by Morandi, he created his own series. Grisha was a theoretical person, he delved a lot into theory and studied different styles.

It was Grisha who supported the general educational level in our republic. He was distinguished by his penetration into some secrets, the depths of representation as such. At least take the example that he paid attention to Malevich’s art much earlier than others.

When Bazhan translated Dante, Grisha was just making illustrations for it. In the end they sounded great. Nikolai Platonovich supported Grisha.

Works: Giorgio Morandi

— Apart from his own searches in art, what kind of personality was Gavrilenko?

— Grisha was a very bright personality and at the same time he was calm and self-possessed, a minimalist in everything. He was a man with very strong, absolute foundations: masculine and human. This reflected the fact that Grisha was very decent and fair. His justice was the highest.

When there was no longer any strength to argue, they turned to him as an arbitrator, and Grisha made a decision. I repeat, for us he was the highest authority, and we loved him very much. I had a very close relationship with him.

Grisha was a very bright personality and at the same time he was calm and self-possessed, a minimalist in everything.

— What ideas did your generation live at that time?

— We had an idol then – Roger Garaudy. It so happened that we accidentally received his brochure, since it was banned in the USSR. The brochure was called “Realism Without Shores.”

The ideas that there are no restrictions for realism, that it is a broad concept in itself, really appealed to us. The brochure said that, among other things, impressionists and cubists were also involved in realism. Actually, based on the ideas expressed in the brochure, everything that is figurative automatically represents realism.

You need to understand that we denied socialist realism, but professed “Realism without shores.” When we lived in the Via del Corno Republic, Roger Garaudy was our temporary ideologist.

— It is known that there were many guests in the house on Kudryavskaya. Can you tell us what kind of people they were?

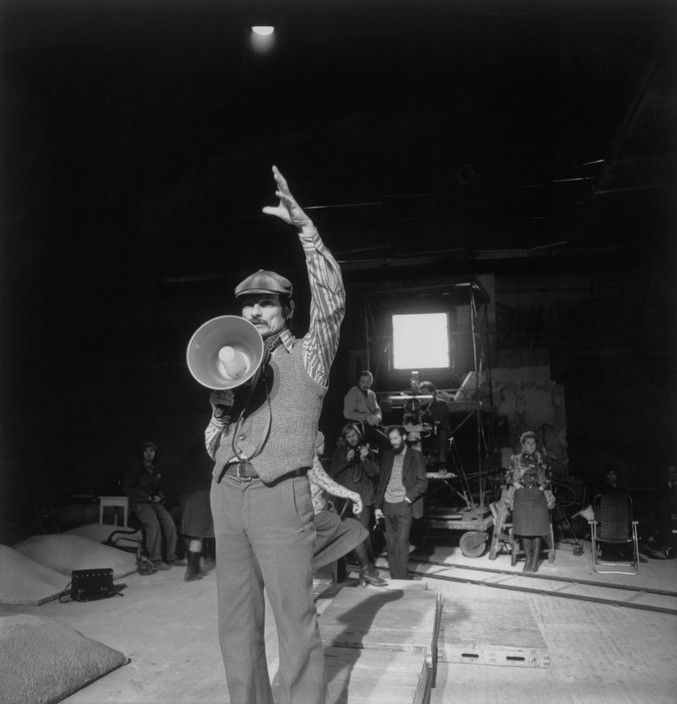

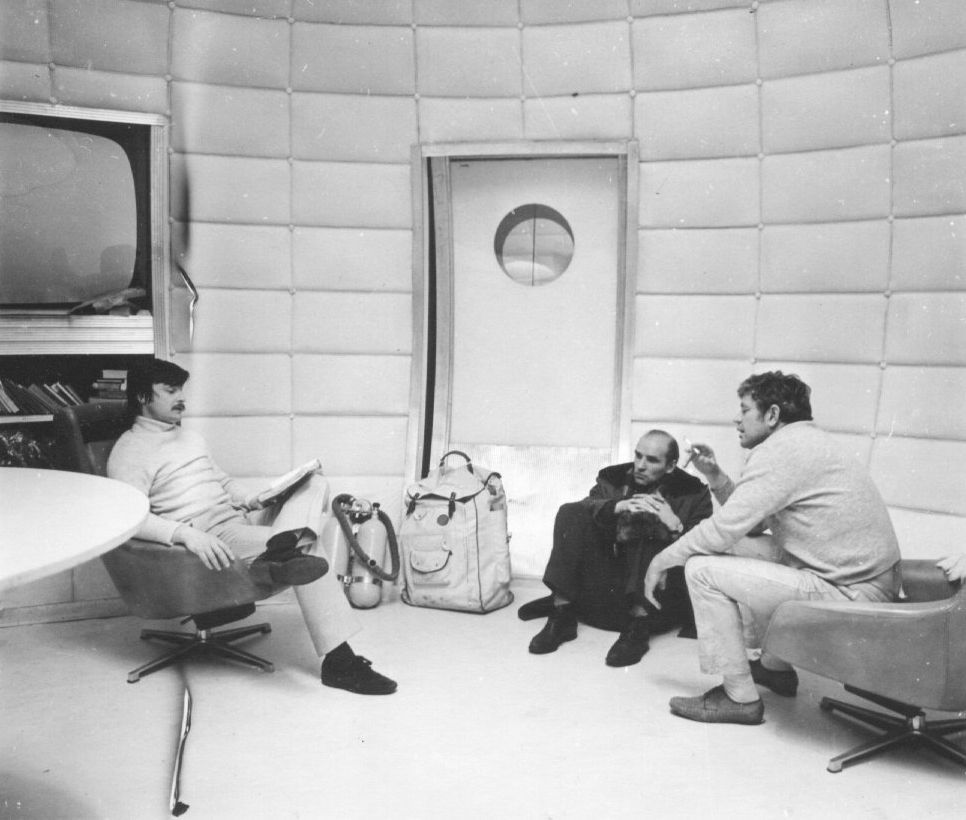

— It started when Yura (George) participated in the production of the film “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.” In it, Yakutovich was the main artist. Actually, I went to the filming of the film, and the film crew itself came to us at Kudryavskaya, where we had a feast. This is how I met Parajanov, Vanya Mykolaichuk, Ivan Gavrilyuk, Kostya Stepanov and Ilyenok. It was one company.

God, what feasts we had then, what a miracle it was. In general, we lived a stormy, incredibly interesting life. We were young, self-confident, impetuous. Yura and I flew to the Carpathians; in addition, we flew to Solovki, where we went to look for traces of Kurbas and find out more about the circumstances in which he died. When we were young, we had amazing liveliness.

— What kind of relationships, in general, were there between the residents of the republic?

— We were all like brothers.” Until our death, we were united by an incredible spiritual kinship. These were all loved ones. The atmosphere in which we lived is simply difficult to imagine.

At some point, Parajanov got involved in all this. He was subject to our influence, and we saturated him with real communication. In the circle of our republic, he discovered a lot for himself, he became somewhat different: more tolerant, more profound. I say this because I watched him for a long time, because we were friends for a long time.

— How did it happen that you became interested in the personality of Kurbas?

— It so happened that a strange person told me about Kurbas, and in our circles there were suspicions that he was an informer. In any case, he was educated and it was from him that I first heard the name Kurbas.

At that time, I was just teaching at the Lavra school. One day, I was walking to work and on the way a man approached me and invited me to a lecture about Kurbas. The fact is that the film department of the theater institute was located in one of the premises of the Lavra. At that time, his last name didn’t mean anything to me and this man told me that Kurbas was an amazingly brilliant director to whom Mayerhold doffed his hat.

I was not able to attend this lecture, but since then I have been terribly interested in his personality and today my monument dedicated to him stands on Proriznaya.

Kurbas is an amazingly brilliant director, to whom Mayerhold doffed his hat.

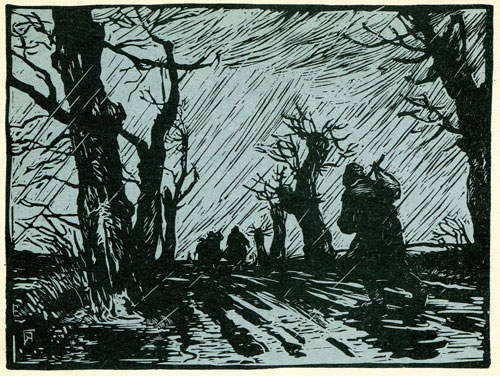

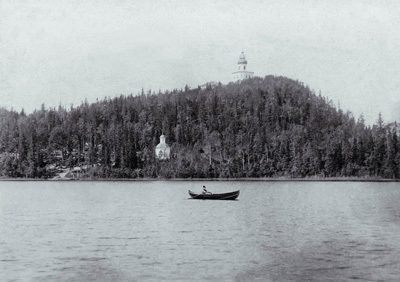

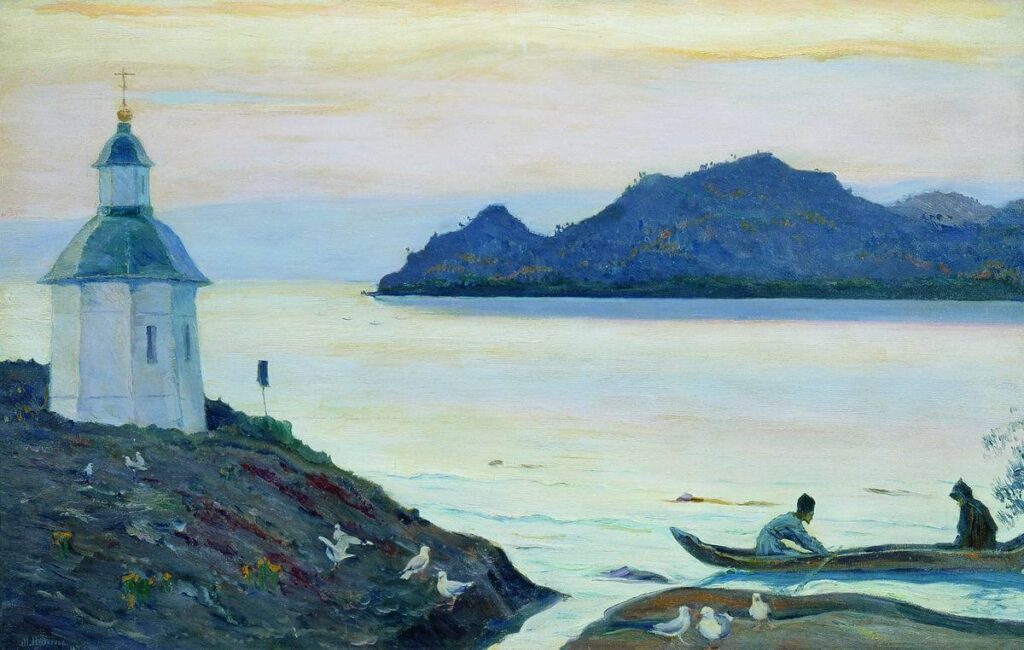

Solovki

Writers Mykola Zerov, Mykola Kulish, Yevgeny Pluzhnyk, Valerian Pidmogilny, director Les Kurbas, Prime Minister of the Ukrainian People’s Republic Volodymyr Chekhivskyi, and Minister of Finance of the Ukrainian SSR Mykhailo Poloz were executed on the Solovetsky Islands.

— How did you get the idea to visit Solovki?

— It is worth noting that we planned a trip to Solovki in 1964: this was the first year when they became open to the public. When Yura and I came up with this idea, I told him about Kurbas, and he became no less interested in his fate than I was. Before this, Yura had not heard of him, since he was shot, and it was a closed surname. In general, after he was sent to Solovki, he fell silent, and not a word about him was published anywhere.

— Before continuing the topic of Solovki, could you briefly tell us about them for our readers?

— Solovki is an entire archipelago of concentration camps, organized by Lenin in 1920. It was a scary place where terrible things happened. The Solovetsky camps were liquidated only after the start of the war in 1939.

— In the end, did you learn something about the fate of Kurbas on Solovki?

— We stayed on the Solovetsky Islands for ten days, but we never learned anything about Kurbas. There was a rumor that in 1939, when the camps were liquidated, all the prisoners were put on a barge and drowned in the White Sea. However, later one person – after serving his sentence – said that he saw Kurbas in Kolyma. According to him, the barge in which Kurbas was located was sent along the Northern Sea Route to Kolyma, where he died in 1942.

— What did you take away from this trip?

— In fact, before visiting Solovki, we had no idea about the scale of the repressions. We explored many islands and visited places where camps were located.

— What is the first thing that catches your eye when you come to Solovki?

— Immediately upon arrival in the Solovetsky village, we saw the Transfiguration Cathedral, which at that time served as a dining room. In fact, the domes were removed from the cathedral and a dining room was made for sailors. After the liquidation of the camps in these parts, a school of sea cabin boys was founded.

Among other places, the famous Sekirnaya Mountain was remembered. This is a place where people were interrogated, tortured and shot. Now there is a small chapel on this site.

— If we talk about local nature, at the same time about the sensations that those places evoke?

— As for nature, you need to understand that this is the north, where nature is harsh and at the same time majestic. At the same time, if we talk about feelings, after hearing about mass shootings, a feeling of incredible depression arose. It’s hard to even imagine what happened on Solovki about 100 years ago.

— Perhaps you managed to learn something else interesting on this trip?

— Local people told me something. For example, the woman who delivered milk was the wife of a camp guard. This woman showed us the cell in which the last ataman of the Zaporozhye Sich, Petro Ivanovich Kalnyshevsky, was sitting.

The cell in which he sat for the last 12 years of his sentence was small, and it was possible to enter it only by bending his head. The room had a small stone rookery and a small window overlooking the cemetery and graves.

Unfortunately, the cell was not the scariest place, because before that he was simply kept in a hole. It is difficult to imagine what inhuman conditions these were. They say he was released at the age of 108 and died 4 years later.

— No, it was the courtyard of the monastery, where you could see a huge number of cells. At first these were monastic cells, which later became cells for prisoners.

— No, it was the courtyard of the monastery, where you could see a huge number of cells. At first these were monastic cells, which later became cells for prisoners.

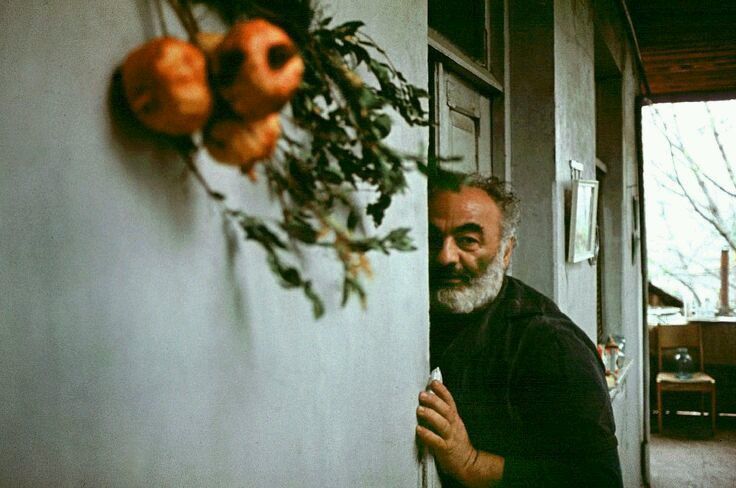

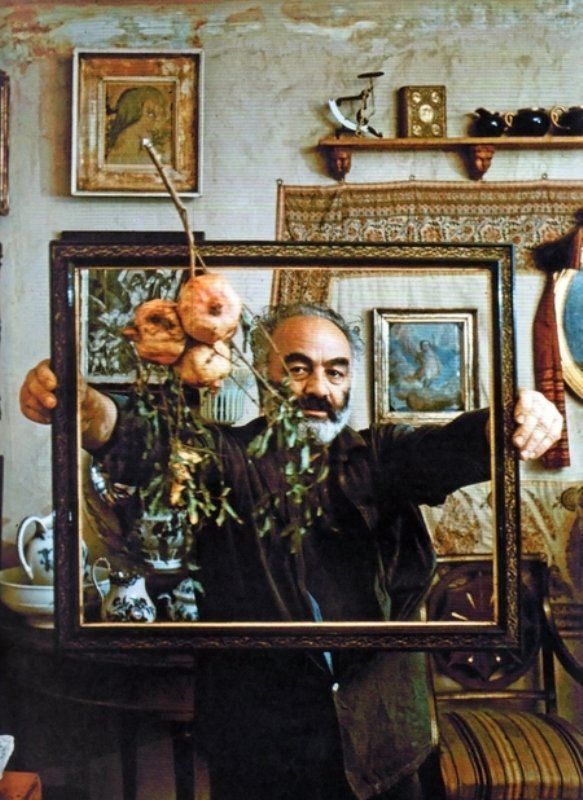

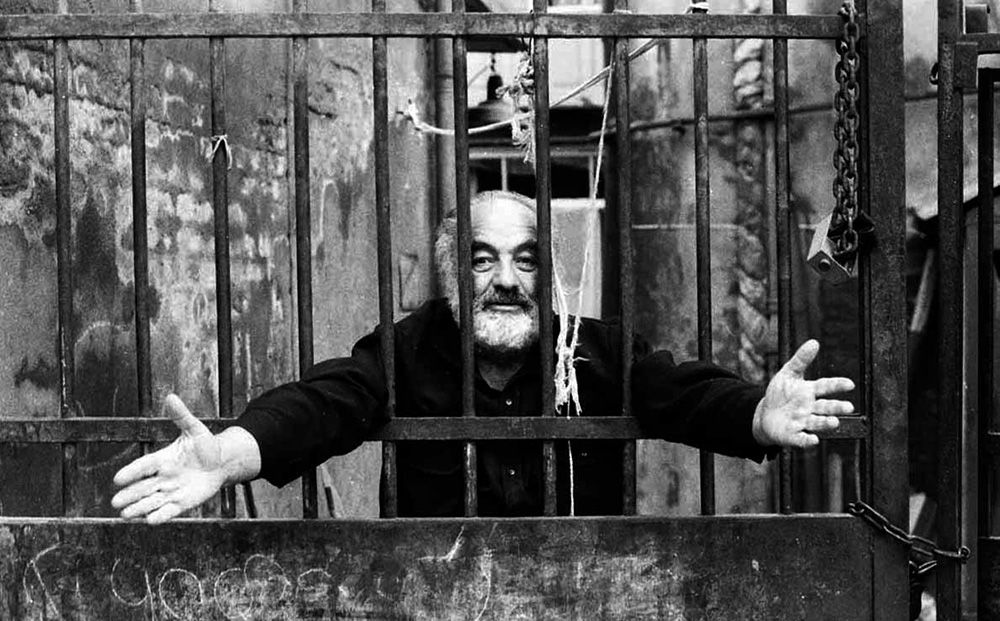

Paradzhanov

— Tell us about your friendship with Parajanov.

— The manifestation of his personality in Kyiv is very significant. In addition, I can definitely say that Parajanov cannot be compared, he was so unique and original.

We met at Parajanov’s almost every evening. I finished work and went to see him on Victory Square. Before leaving, he called me and said: “Kolya, grab some bread and cheese on the way, grab something to snack on and come.” Thus, someone brought food, someone brought vodka, someone brought wine – and we sat down at the table. Seryozha was an amazing person in this regard – as hospitable as a Caucasian.

Parajanov was so original and unique that he cannot be compared.

— Could you say what kind of person Parajanov was?

— I communicated with Parajanov for several years with almost constant regularity. However, I cannot say that I know Parajanov’s formula. Like, that’s exactly who he is and that’s it. He could be anyone, so he is everyone, he is infinite. Parajanov was so diverse that I cannot undertake to put all his manifestations together and say what he was like.

I can’t say that I know Parajanov’s formula. He could be anyone, so he is everyone, he is infinite.

— It is known that Parajanov’s films were repeatedly refused to be made. On what means did he live when he found himself in such circumstances?

— When there was no income, Georgians came to him, with whom he traded. Parajanov resold antiques that he searched for in apartments and flea markets. He often sold furniture. He sold these things to Georgians at exorbitant prices, and we then went on a spree with this money.

— Your environment and you yourself did not live in luxury and did not put material wealth above all else, right?

— We believed that we only needed money for the essentials of life: food, rent and clothing. We had no desire to earn money, the main thing was to make art. We viewed our occupation as a service to art: this is exactly how the professors raised me in Odessa.

We had no desire to earn money, the main thing was to make art.

— In general, did Parajanov have many guests?

— People always came to him, and in huge numbers. When you don’t come, the apartment is literally packed with people, by the way, not only inside, but there were also even people standing in the corridor. His apartment was a place of enormous cultural connection and art. Everyone gathered with him: poets, artists, composers, directors. Everyone found their place there. Many people came to see him, and his apartment seemed to become a place of pilgrimage. It was all so natural that it frightened the KGB, frightened the authorities.

— Tell me, how did you survive his arrest?

— His arrest was a real tragedy, it looked quite creepy, even ominous. They imprisoned a man who was completely innocent, but at the same time they arrested him – and they accused him of outright nonsense. Apparently, this is an order from the Central Committee: to imprison by any means necessary.

At first, he was given a trade in diamonds and various precious stones. In the process of searching for evidence in Sergei’s apartment, all the baseboards were blown up. Of course, the investigators found nothing, because there were no stones anywhere nearby. In the end, homosexuality was taught to him, and it was on this basis that he was imprisoned.

Such world-famous directors as Jean-Luc Godard, Federico Fellini, Roberto Rossellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Andriy Tarkovsky, poet Louis Aragon spoke with a call to release Parajanov from prison.

— In fact, the reason for the arrest was that he allowed himself to openly criticize the Soviet regime?

— Indeed, Parajanov openly criticized the Soviet regime and spoke sharply about it. Meanwhile, he did not understand why he was not allowed to go abroad. His films are shown abroad and in the Union, Ivan Mikolaichuk and Larisa Kadochnikova receive awards instead of him, and he sits at home.

He was two heads taller than them, so highly developed was his human understanding and awareness of what needed to be done to accomplish a particular task. He had a tremendously intelligent, practical head and talent as an organizer.

Although, on the one hand, he was a careless and chaotic person, this did not prevent him from having a strict, efficient mind. He did not understand why and why he was being discriminated against, and one could repeatedly hear from him: “They don’t understand, I’m more of a communist than they are.” And this despite the fact that he was not a communist.

“Please inform your readers that I died in 1968 due to the genocidal policies of the Soviet regime.”

— Speaking specifically about you, what was your attitude towards the party?

— I would call myself an internal oppositionist, because outwardly I did not try to emphasize this and contrast myself with anyone. Only in our circle we could afford to make fun of the party. In general, I did not like the party, and when I was offered to join it, I refused because I knew its value. I considered having a party card as “earning money.” In addition, I did not want to take on moral responsibility, which at that time already lay with the party.

When I was offered to join the party, I refused because I knew its value. I considered having a party card as “earning money.”

— Was it possible to live in Soviet times in such a way as not to feel the pressure of the party?

— These were the times of my youth, and whatever power there was, it faded into the background. We simply lived in conditions that we took for granted. At times we were poor and hungry, and when food appeared, we ate too much. At the same time, we were friends and loved, however, as at all times.

Before getting married, it seemed to me that I was completely free. Probably because I was never afraid to do what I really wanted. Of course, we are talking about choosing from what was allowed. Moreover, it doesn’t matter: in childhood, youth or adolescence.

Of course, the repressions affected a friend close to me, as well as a relative on my wife’s side, but personally, the tragic side of the regime did not greatly affect me.

It seemed to me that I was completely free. Probably because I was never afraid to do what I really wanted.

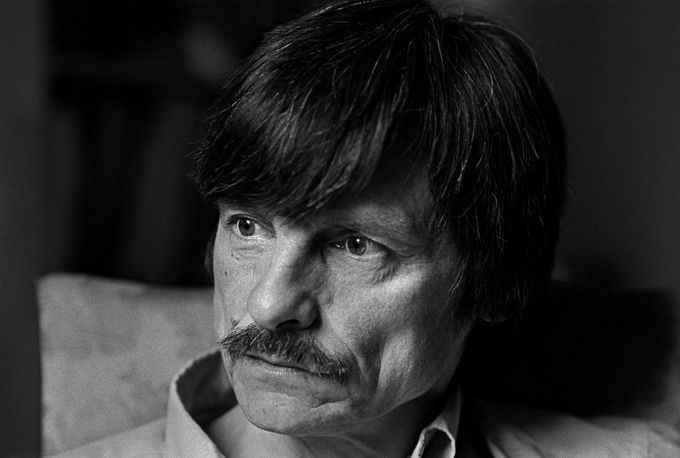

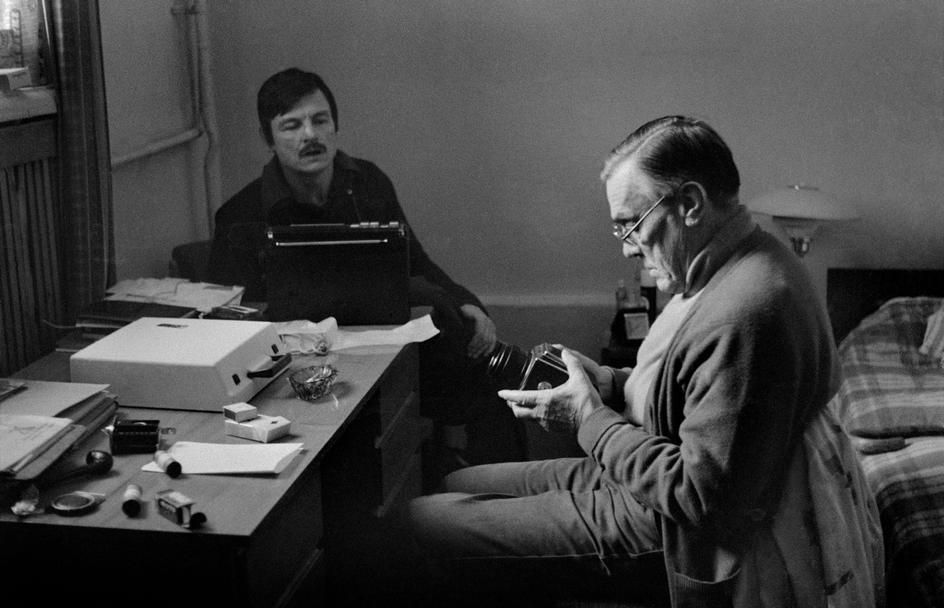

Tarkovsky

— It is known that Parajanov knew Andrei Tarkovsky. Perhaps you were also familiar with him?

— It happened. One day Parajanov calls me and says: “Tomorrow we are going to watch a Tarkovsky film at the Dovzhenko film studio.” I remember that the film was shown in a large screening room so that more people could see it.

After the end of the film, Sergei takes me to Tarkovsky and says: “Let’s go to my home now, to Victory Square, we’ll have lunch and talk about everything.” Tarkovsky agrees with pleasure, and we go to him. It was about three or four o’clock.

— What atmosphere did you spend time in, what did you talk about?

— We discussed Tarkovsky’s film “Andrei Rublev,” which we really liked, and slowly drank wine. Our communication with Tarkovsky took place in an amazingly beautiful atmosphere: euphoria of friendship, delight and a certain intimacy.

He said that after filming the film was banned, they were not allowed to rent it, in a word, they put it on the shelf. However, after a while they called him and said: “You can show the film at public screenings, anywhere, throughout the Soviet Union.” It is worth noting that absolutely no changes were made.

After which he sends an application to Kyiv, in response to which he is sent an invitation to Kyiv with a creative show.

Our communication with Tarkovsky took place in an amazingly beautiful atmosphere: euphoria of friendship, delight and a certain intimacy.

— What else did Tarkovsky talk about?

— At some point Andrei says: “Now I’ll read a chapter from the film that I’m about to shoot, called “Mirror”.” It looked very cool, I was in a state of euphoria.

Memories of this episode by Anna Parajanova:

“At some point, Parajanov began to walk from one room to another, and Andrei, meanwhile, read: “Mom washes her hair in rainwater…” I see that Parajanov began to get nervous. And suddenly he appears from the next room and slyly asks: “Andrey, please tell me, what color did the water in the basin turn out to be after mom washed her hair?” Tarkovsky was taken aback. Parajanov said: “If you make a movie of this level, then the waters must change.”

Excerpt from the film “Mirror” by Andrei Tarkovsky, poems read by Arseniy Tarkovsky

— What was Parajanov talking about?

— After this, Parajanov read a chapter of the script from his last film, “Confession,” which he was never destined to complete. I remember that it was about a guy who works as a mason in a cemetery, cutting down monuments.

In general, an interesting premise. I remember that Tarkovsky really liked it. As Seryozha said, this film was supposed to be a confession of his life, starting from childhood. In my opinion, the script was simply brilliantly written, if he did make this film, it would be amazing. This script should be somewhere in Parajanov’s museum.

The film “Confession” was supposed to be a confession of his life, starting from childhood.

— How did the evening end?

— At about twelve o’clock Andrei says that he needs to go. As a souvenir, Sergei gives him a samovar, round in shape. In addition to being stylish, it also dated from the end of the 19th century.

Andrey and I were on the same path. He then stayed at the Moscow Hotel (now the Ukraine Hotel), and I had to go to Pechersk.

We had already gone outside and approached the road to stop the car. I remember this picture: Andrey is holding a samovar in his hands, a gift from Parajanov, it’s very cold outside, it’s still winter, we’re standing, waiting in the cold, but there are still no cars.

— How did you get home?

— At some point, a car appeared from the side of the Shulyavsky Bridge. I wave my hand to the driver, and I see the “bad guy” stops. I see a cop sitting behind the wheel. I ask him: “Will you take us? A famous director from Moscow has come to visit us.” I remember Seryozha complemented me by inserting the word “brilliant”.

He picked us up and first took Andrei to the hotel, and then me to Kikvidze.

He says: “Come on, sit down.” He drove us there without incident, I said goodbye to Andrey and gave the cop a tenner. Everyone was happy: he was happy that he received the money, and we were happy that we caught the car at a late time.

— What kind of person did Tarkovsky seem to you?

— I thought Andrey was very nice, open and cheerful. It seemed that this was a man from our Kyiv environment, as they say, “our man.” In our environment, he behaved relaxed, was open, and fantasized out loud. It cannot be said that he is a “buka” – a closed person. Absolutely not.

Many say that he was unsociable. It may well be that someone simply encountered him in a different environment, and therefore he made a different impression. When I heard about him from others, I couldn’t believe that it was about Andrey – it seemed to me so much that he was a nice person.

It is clear that he was a complex person who behaved differently with different people. There were rumors that he humiliated people on set. I think that was the case. I got the impression that he is basically an arrogant person, so to speak, by nature.

Tarkovsky was a complex person who behaved differently with different people

— Based on what, do you make such conclusions?

— It so happened that I ran into his father, Arseny. He made a similar impression on me, as did Andrey. However, for Arseny this is not arrogance, but self-esteem. This feeling is typical of experienced people who have had to endure a lot. For example, Arseny went through the front and was left without a leg.

I saw this quality in his father and realized that this was also inherent in Andrei. He was sure that he was creating high and deep art. Not everyone is able to objectively see their own art from the outside. It seems to me that Andrei had the feeling that he was doing very deep things and could not do otherwise.

Tarkovsky was sure that he was creating high and deep art. Not everyone is able to objectively see their own art from the outside.

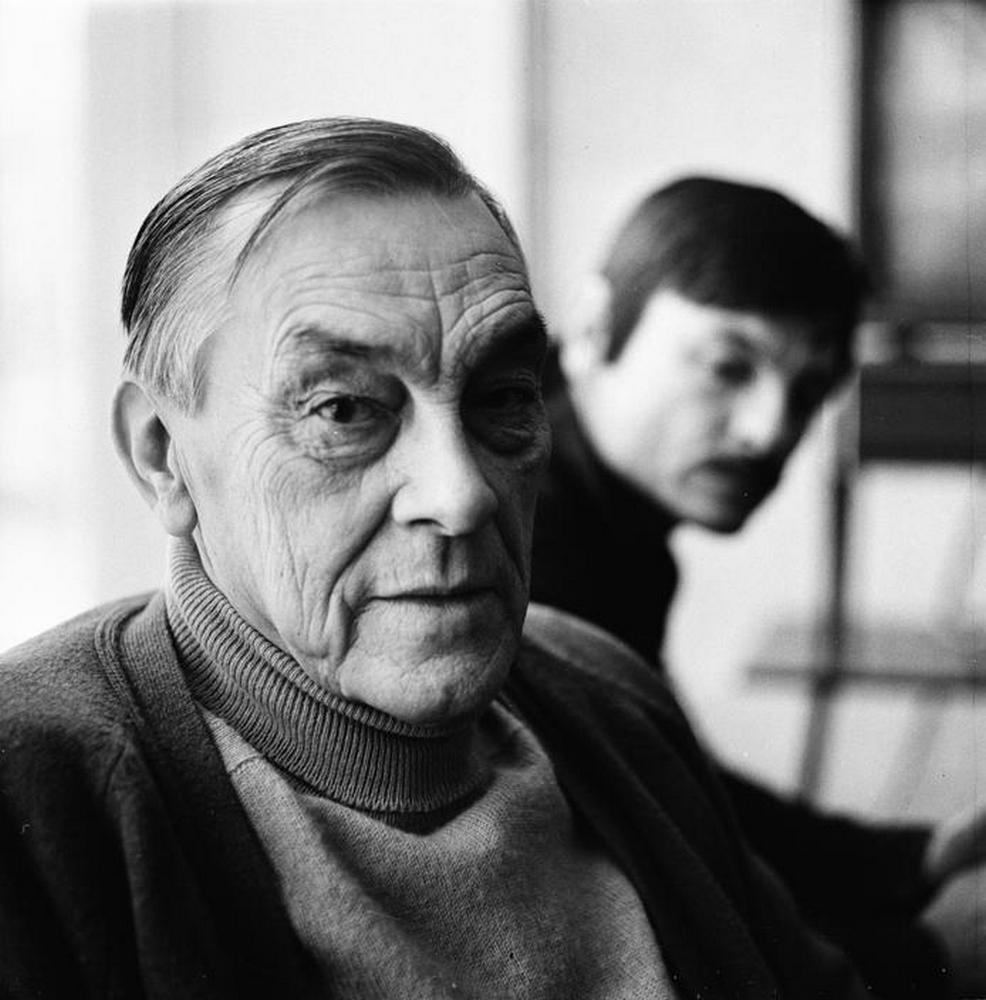

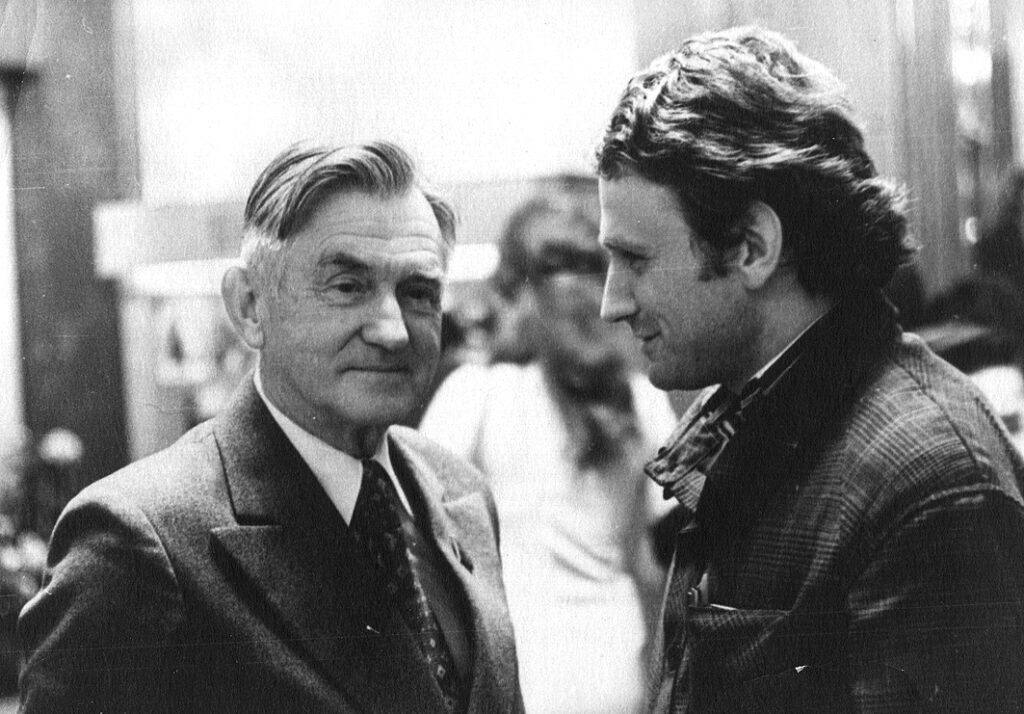

Tarkovskys: Arseny (Father) with Andrei (Son).

Photo: Pinterest

— Where did you meet Arseny Tarkovsky?

— Actually, just like my meeting with Andrey, my meeting with Arseny happened absolutely by accident. We saw him at a feast in Moscow. It was an evening in memory of one Moscow poet Perets Markish, who was the father of my wife. At this evening was Sergei Narovchatov, a poet, secretary of the Writers’ Union. Like Arseny, he was a pretty good poet and front-line soldier. There was also the writer Viktor Shklovsky.

There were quite a lot of people at the feast, but it was Arseny who stood out to me. I sat opposite him and saw in front of me a parchment face – a man drinking quite a lot. Apparently he loved this business. He sat next to Zoya Kozakova, the wife of the Stalin Prize winner. They spoke to each other in French, chatted casually, and joked.

I didn’t really delve into the conversation, but it was very interesting for me to observe this handsome type – an intelligent elderly man. He had a typical noble face, as if he had the stamp of a good breed on him.

— Did his face attract you as a sculptor?

— Exactly, I looked at him and thought I wish I could make a portrait of him.” Later I wanted to do it from memory, but never got around to it.

— It is known that Tarkovsky’s initial attitude towards Parajanov was not the warmest. Perhaps you know a little more about this?

— Indeed, at first Tarkovsky did not accept Parajanov’s films. In general, I treated Serezha’s work carelessly. It was only when he visited Sergei that he saw with his own eyes that Parajanov was an incredibly talented person. The most important thing: he realized that a person like Parajanov could not do a random thing. I think after that Tarkovsky watched his films more than once.

— Why do you think Tarkovsky initially had such an attitude towards Parajanov?

— I think that at first he treated Parajanov with disdain and arrogance, because this, they say, is a province, some kind of Kiev studio. At that time this was the standard approach of the “Moscow masters”.

This attitude was not because this is Ukraine, but because we made weak films, that is, as a rule, they produced mediocre films. Everything that was not approved in Moscow took place here. In the case of the Minsk studio it was the same, and in general, in fact, all republican studios made mediocre films. It was only by chance that stunning films were shot in Kyiv, first by Dovzhenk, then by Parajanov and Balayan.

You need to understand that in Moscow they did exquisite things, that is, they only seriously drove. Even if consumer goods were made, they were of high quality. It is worth considering how many ideal films were shot at Mosfilm. All Soviet elite cinematography was mainly made in Moscow. In addition, at that time Andrei had already shot the gorgeous film “Ivan’s Childhood,” which won the Grand Prix at the Venice Film Festival, which in itself was phenomenal.

— Still, the Soviet government created all the conditions for the intelligentsia to concentrate in Moscow. Have you observed this?

— Naturally, the best personnel of the country were concentrated in Moscow. She sucked out all the best that the province had. People were drawn to her because in the provinces they are mute, no one will hear them. Bulgakov was also pulled from this glorious city, because it was there that all the great events took place at that time.

I also communicated a lot with the Moscow environment. In Moscow I had many friends among famous directors, writers, artists, and actors. Despite the fact that I lived and worked in Kyiv, my ties with Moscow were very close. I have many warm memories associated with the Moscow environment of those years, and it was all worthy.

Each group of intellectuals is an incredibly different environment. You need to understand that, first of all, we are talking about people of different make-up, character and temperament. If we talk about talent, then this is an individual matter.

Moscow sucked out all the best that was in the provinces. People were drawn to her because in the provinces they are mute, no one will hear them.

— After this meeting, did Parajanov still remember Tarkovsky?

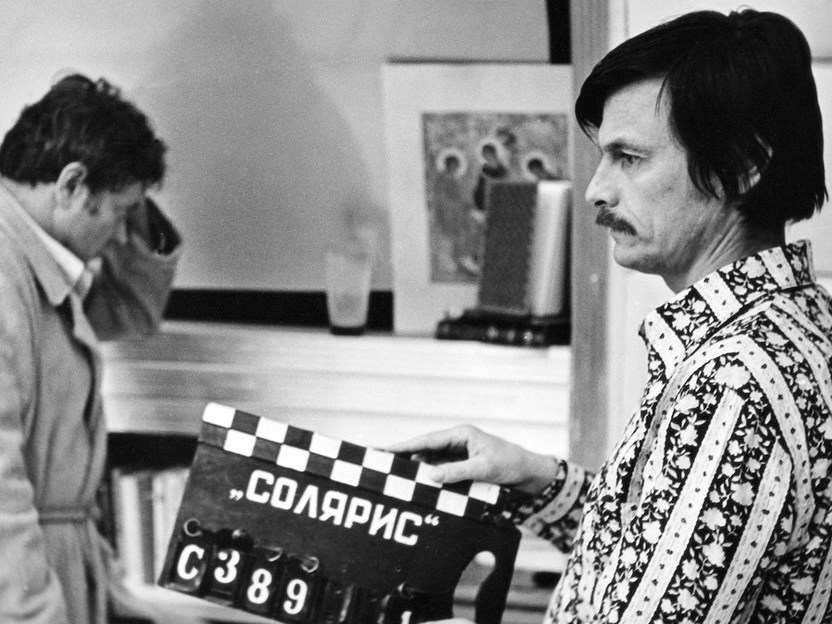

— I remembered it often, but instead I’d rather tell you one incident.” I’m sitting in my workshop on Reitarskaya, working, when suddenly, at about 12 o’clock, Parajanov drops in to see me. I remember how the door suddenly opens and Parajanov for some reason shouts something like: bastard, scum. I ask: Seryozha, what happened? In response I hear: he robbed me. I say: who stole? Answer: Tarkovsky.

Then he tells me: You know, he made the brilliant film “Solaris”. In it, Tarkovsky embodied everything I wanted to do in cinema. There’s nothing left for me to do in the cinema: I’ve been robbed, I’ve been stripped, in the end I’m mediocre, I can’t do anything. It was clear that there was genuine emotion.

I say: Seryozha, what are you saying, calm down. So that Seryozha could come to his senses, I made some tea and while drinking tea he said: Kolya, this is a brilliant film, go watch it. I say: I’m going to watch it with my wife right away tomorrow. Actually, the next day we went and looked.

— Did he share any impressions about the film itself?

— He began to retell the film but could not talk about it coherently. Sergei was impressed by this film, as a result of which he built images that did not correspond to the film at all. “Solaris” turned out to be even stronger than Sergei said. The impressions were so exciting that he could not convey everything.

— After watching, did you share your impressions of the film with Parajanov?

— I really liked this film: its sublimity and cosmic mysticism. I was amazed at how great the film was made: with what means, how amazingly everything was mounted and connected, and how it was shot in general.

The next day in the evening I go to Parajanov and say: “Seryozha, you know, this is a truly brilliant film.” To which he replies: “Kolya, I still can’t calm down, he made such a strong impression on me.”

— Perhaps you could describe a specific moment?

— Parajanov says: “Do you remember how everything is filled with white light? How to achieve this?” The fact is that this film was shot by the brilliant cameraman Vadim Yusov. I believe it was thanks to this seasoned cameraman that he was able to achieve absolutely stunning lighting, as a result of which the film seemed to be filled with the presence of other worlds.

Take this strange cloud separately; it, in fact, was a separate thinking substance. With his help, a mystery was created, but it is difficult to understand by what means it was realized, and this is fantastic. I was also struck by the way the cloud was lowered into the house and the fact that in the house there is a landscape by Bruegel “Return from the Hunt”, which hangs on my wall.

Tarkovsky’s cameraman managed to achieve absolutely stunning lighting, as a result of which the film seemed to be filled with the presence of other worlds.

— What kind of director, in your opinion, was Andrei Tarkovsky, and what is his place in world cinema?

— In his films, Andrei managed to successfully intertwine exquisite things. In his own films, he seemed to sublimate all the best in humanity and cinema. He was the battery of it all, which is why his films are so deep and lasting. In my opinion, this is the highest aerobatics of world culture. I think this is a classic that will live on for a very long time. People will come back to him because he made great films.

In his films, Tarkovsky sublimated all the best in humanity and cinema.

— There is an opinion that Tarkovsky found filmmaking more difficult than Parajanov, and, supposedly, based on this, it was easier for him to create his amazing things. Is it really?

— In general, lightness is a rather conventional concept in art. On the other hand, the pangs of creativity are also not very clear to me. First of all, ease occurs when there is preparedness for the moment of telling. The very moment of telling is when something is directly stated. At the same time, there must be thoughtfulness and some feeling – only then can something go easily.

For example, Parajanov found it very difficult to film his “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.” There were so many difficulties, dramas and screams on the set that there was no smell of ease there. In general, great passions were going on during the filming, and to say that they were easy would not be true. Any film is difficult to make, it requires effort, especially when we are talking about a large number of people who are needed in order to make a quality film.

— Why do you think such an opinion appeared?

— Perhaps because it is much easier to accept a purely superficial view as the truth.” However, in reality everything is more complicated. The fact is that we often see a person in a random mood, and having met a person only once, he may seem angry. It should not be ruled out that the next day you will be able to see this person in a completely different mood, and he will seem completely different to you. This suggests that a person has everything: the first, the second, and the third.

It is much easier to accept a purely superficial view as the truth. In reality, everything is much more complicated.

— What were the differences between the characters of Tarkovsky and Parajanov?

— In my opinion, everything is decided by a person’s mental make-up. Of course, Sergei Parajanov was more open than Andrei Tarkovsky, but this is only because he had different upbringing conditions. He grew up in Tiflis, where all the courtyards were open, and, moreover, in an Armenian family.

In turn, Andrei was brought up in a more closed office environment. His father, Arseny, raised him completely differently. That is why Parajanov’s behavior is more free, democratic, while Tarkovsky’s is more restrained and conservative.

— Can you give an example of how these differences manifested themselves?

— I think Tarkovsky could not afford what Parajanov could afford. Sergei could approach a stranger on the street and tell him that he looks beautiful, and also ask where he dresses. Andrei would never allow himself to do this. Therefore, we can say that they were distinguished by both their upbringing and mental make-up.

Antonov

— It is known that you were friends with aircraft designer Oleg Antonov. Can you share your impressions about it?

— Oleg Konstantinovich Antonov was simply a miracle man. Even on the farm as a boy, I already knew this surname – Antonov. Therefore, when I encountered him in person, it was as if a revelation struck me.

When we were introduced to each other, I told him: “Oleg Konstantinovich, could you pose for me? I would like to take your portrait.” To which he replied: “Please, if you find anything interesting in my face.”

Even on the farm as a boy, I already knew this surname – Antonov. So when I encountered him in person, it was like a revelation struck me.

— What kind of person was he?

— He was very attentive and insightful and had incredible delicacy. I felt very good with him, he was so natural that, being next to him, I felt extremely relaxed.

As a result, we became close friends. At the very beginning of our friendship, I was invited to his 70th birthday. It often happened that he would pick me up at the workshop in his Volga and offer to go somewhere to eat. I understood that he wanted communication outside of work and family.

In terms of the opposite sex, he was sensual and playful, adored beautiful women and was generally a man of all kinds.

— If we talk specifically about cultural terms?

— He was a very cultured man, he loved painting and literature. He and I often talked about literature, discussing some of our favorite things. He also loved painting and even drew a little. Even if it turned out amateurish, he liked to draw. He showed me his work.

— Did Antonov have a certain unique approach to people?

— He had a creed through which he saw people. Somehow during a conversation

he tells me: “I divide people into acquirers and inventors.” According to him, there are people who want everything only for themselves, but there are also those who can share and give of themselves at any time.

Antonov: “I divide people into acquirers and inventors.”

— Under what circumstances did you last communicate?

— I remember our last conversation. One summer I caught myself thinking that Oleg Konstantinovich had not visited me for a long time. I also thought to myself: maybe something happened to him?

I called him and said: “Oleg Konstantinovich, where have you gone?” He replies: “You see, dear, I’m in the hospital all the time and by chance I ended up at home, they just let me go on the day off. Even the children didn’t expect me to come; they were at the dacha when the ambulance brought me. The hospital said that I would be discharged soon, and as soon as I am home, I will contact you and we will definitely meet.” After which he hung up.

A month later, I hear an announcement on the radio that the great aircraft designer Oleg Antonov has died. At first, I didn’t understand: how did he die? I just spoke to him recently. It was a big loss for me; he was very dear to me. We were friends with him for eight years, and he died in the 79th year.

Kyiv

— You lived in Kyiv for many years. Share your perception of the city?

— For me, Kyiv embodies the life I lived there and the people I loved here and still love. During the time I lived here, I developed certain well-established and simulated visual images, changes, surroundings, landscapes of the city streets. Kyiv is very beautiful, just neglected. If it were put in order, we could say that this is not just another wonderful city, but one of the best in Europe.

If Kyiv is put in order, we could say that it is not just another wonderful city, but one of the best in Europe.

— If you managed to visit abroad, what impression did European capitals make on you?

— Having been abroad, visiting Paris, London and Vienna, I was struck by their well-groomed and cleanliness. It is immediately noticeable that the city’s microstructures and park architecture have been put in order.

If we put our hands to it, a huge number of opportunities to create beauty will open up before us. You just need to succinctly play with modern and old architecture and keep the streets clean. In short, we need to create all the conditions so that people, walking around the city, admire it and rejoice in what they see. Nowadays, many urban spaces resemble a battered train station. Neglect spoils Kyiv, but the city itself is very beautiful.

If we put our hands to it, a huge number of opportunities to create beauty will open up before us.

— What does it mean to you to be a resident of Kyivian?

— In order to be a real Kievite, in addition to the fact that, of course, you need to live in Kyiv, you also need to do something for it. At least try.

A Kievite is a person who loves Kyiv and wants it to be better. Being a Kyivian resident is not about consumption: someone will do it for me, and I will use it. I would like people to be not indifferent to the city and work to improve it.

A Kievman is a person who loves Kyiv and wants it to be better.

— How do you perceive Kyiv in the format of permanent high-rise development?

— Kyiv has been constantly changed, but I accept it as it is. Everything that is created in Kyiv, the same skyscrapers, are built only because such a course of things dictates life. Actually, everything that is happening in Kyiv here and now is reality, it is a city. It should be borne in mind that all cities are developing and built up. If people find opportunities to build it, I can’t resist it.

— Do you think that it is possible to successfully combine architectural heritage with what is being built today?

— When I was in Vienna, I saw a glass four-story banner building like the Kyiv Hayat standing near the 11th-century St. Stephen’s Cathedral. I saw with my own eyes how beautifully Stephen’s Cathedral is reflected in it with the help of different rays of light. It’s great when something modern harmoniously combines with the 11th century.

The city should not freeze in one style, in one era. The second thing: you need to build a garden wisely, and at the same time, it is also tasty. Modern architects need to learn to skillfully paste and place modern buildings in such a way that they do not destroy the structure of the old city.

The city should not freeze in one style and one era

— In which Kyiv cafes or restaurants did you meet with friends during the Soviet era?

— Although restaurants were relatively affordable in Soviet times, we still often went to each other’s homes.

However, there was a time when, on weekends, the whole family went to the Dinamo restaurant, which was located not far from the Lobanovskyi Stadium. It was a solid restaurant that enjoyed great popularity, and also indulged in good cuisine. This was a place where you could come both for a holiday and just to chat.

I still remember how I went for lunch with a friend to the “Teatralny” restaurant, where it was possible to meet Stalin’s laureate Reznichenko. At that time, I worked in my first workshop on Reitarskaya.

— What streets do you like most in Kyiv?

— I like Yaroslavov Val, Reitarskaya and Streletskaya the most. At the same time, I also like the central streets, such as Vladimirskaya and Khreshchatyk.

Art

— What did you want to express with your sculpture?

— It is almost impossible to explain my attitude to sculpture. Doing sculpture, I wanted to understand a person, to understand who he is. While working on portraits, I noticed that a person’s face changes in every way during the work. When he sits down to pose, he is alone, after a while he becomes the second, coming tomorrow, he is already someone third. Based on this, I wanted to understand what he is like? What is his true manifestation, what is most characteristic of him and what is most important to him.

For myself, I decided that life should be present in my sculpture, moreover, awe for life should be visible. Such things are achieved intuitively. There is a bit of mystery in this work.

— Today, would you like to portray someone?

— I didn’t think about it. Now my hands are shaking, and, as a result, I have lost interest in it, my passion for portraiture has ended. Previously, it was my main task to depict what the established personalities who were significant in my time looked like, and, in general, it seemed very necessary to me. I saw the meaning of my life in leaving the monuments of these worthy people for posterity.

When you look at the portraits of Caligula and Mark Antony, you can understand how interesting their personalities were. When looking at a portrait, I am looking for a representation of the qualities that were in this person. It is typical for Roman sculptors of that time to depict portraits with artistic accuracy, but not naturalness. At the same time, if the person had flaws, they did not hide them. I liked the truth of this.

I followed these principles in my work. I wanted to find some kind of salt in the person whom I depicted in the sculpture. My interest was fueled by the fact that I knew: the people I model are usually large, established individuals who have achievements in their field.

— Who are your favorite sculptors?

— My favorite sculptors from the era of high classics: Romans, Greeks, Egyptians. Among my favorite sculptors, I can single out Phidias and Polykletos. I like the numb grandeur they created.

The sculpture of the Greeks was characterized by freedom and beauty. In turn, the sculpture of the Romans is very elegant, their language is refined. Roman sculpture expressed the spirit of the people. The people themselves at that time were driven and focused on victory, on maintaining the greatness of the country, on educating the citizens of the state.

It should be understood that in ancient times, sculpture was not a means, but the result of a state of mind.

On the left – a sculpture created by Polycletus, on the right – Phidias

Photo: Pinterest

In ancient times, sculpture was not a means, but the result of a state of mind.

— Did the same Romans not have errors in relation to art?

— The Romans also behaved abominably. When a new emperor came, the monuments built by the previous ruler were demolished. Such an approach is nothing but vandalism, and the internal vandalism of people who professed similar approaches. Sometimes we are dealing with people who do not feel love for both a living person and his image in paintings and sculptures.

I am not a supporter of the destruction of ancient monuments and curse the people who destroyed ancient monuments. This is a topic of society’s culture; however, politics is brought into it. In turn, the sculpture perpetuates personalities who are significant for the city in which they lived, the nation, and sometimes even for the whole world. That is why I created monuments to Bulgakov and Kurbas.

Sometimes, we are dealing with people who do not feel love for both a living person and his image in painting and sculpture.

— What would you say about the monuments to Lenin, which used to be in every city and every village?

— The fact is that the Bolsheviks adopted sculpture as a means. When the Soviet government riveted Lenins into every farmstead, it was nothing more than a means of suppressing the people. The ubiquitous presence of the so-called leader is an insane, totalitarian and completely anti-people principle.

— You have devoted your entire life to serving art. Tell us what you mean by this concept?

— Art is a huge exciting layer, but few people use it. I believe that a person who is familiar with art, who feels and loves it, cherishes a lot of good things in himself. Art invisibly cultivates kindness in a person. After which he becomes more attentive and responsive. As for me, art is pure kindness.

All aspects of art, no matter fine art or theater, are aimed at bringing out the best in a person. Ultimately, it is very important for an artist to have a wide mental range, and culture in the broad sense of the word means a lot.

All aspects of art, no matter fine art or theater, are aimed at awakening the best in a person.

— Have you ever wondered how to make art understandable to a wide range of people?

— Unfortunately, the position that art should be for the masses, in my opinion, is wrong. For example, at one time they tried to make cinema an art for the masses. However, it turned out that good cinema, which can be called art, is far from being for the masses.

Everything that is created exclusively for the broad masses is consumer goods in its purest form.

Culture is created for people who are ready to perceive it. Of course, there are genres of art that are more often accepted, but one way or another they are of little concern to all other branches of art. We are talking about various delights, deepening of art. This is why art is not for the masses.

Culture is created for people who are ready to perceive it

— What is your attitude towards contemporary art?

— Contemporary art is dying precisely because it is commercial. Yes, today we must admit that art has turned into commerce and at the same time has literally fallen to the bottom. Sometimes it seems to me that there is no longer any art. You can’t keep in mind only the commercial side; such an approach is contraindicated for art.

Based on these considerations, I advise you to avoid excessive commercialism and create art according to how you understand and feel it. We need to create beauty, not put rotten carcasses on display in a museum.

— In your opinion, is everything really that bad with contemporary art?

— I believe that the period in which we live will be called a period of decline. As for me, this is exactly how what is happening in the world will be perceived. However, I believe that art will still rise and find a form of expression for the enthusiastic principle in man. It is both positive and aesthetic. As for me, real art is designed to convey enthusiasm and joy, but not the opposite.

Real art is designed to convey enthusiasm and joy, but not the opposite.

— Is it art that brings you the greatest inspiration in life?

— Indeed, art brings me the greatest joy in life.” We are talking about the entire abundance of art created in the world. When gracefully shaped, art is a bottomless well of inspiration.

When you get acquainted with art, you begin to feel shocks within yourself. Also, writers first read what they like, and then they themselves want to write something. This is an absolutely natural process that makes up a system of daily creativity. You need to keep in mind that it is difficult to be inspired by your own creativity. Typically, we are inspired by other people’s art.

Art is a bottomless well of inspiration.

— Finally, tell us about your series of artistic works “Search for Truth.” What meaning did you put into it?

— Now I understand that the very name “Search for Truth” sounds too pretentious. Rather, I meant touching the truth. The fact is that we are always looking for the truth, but we never find it.

In this series of works, I wanted to consider the earthly life of Christ through the prism of the legends told about him. I mean the Bible and the Gospel. I am amazed by the personality of Christ; he was definitely a person of high class, of high spiritual flight. I think he is more than a philosopher, because, in addition to philosophy, he combined the talent of insight, awe of life and, of course, high spirituality. Often people do not have a combination of these qualities.

The earthly life of Christ seems to me to be true. However, this series of works represents nothing more than an attempt to comprehend the earthly processes associated with his personality.

We are always looking for the truth but we never find it

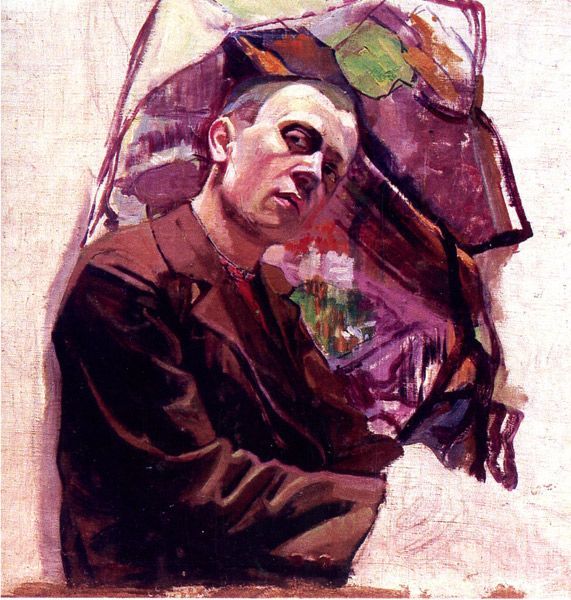

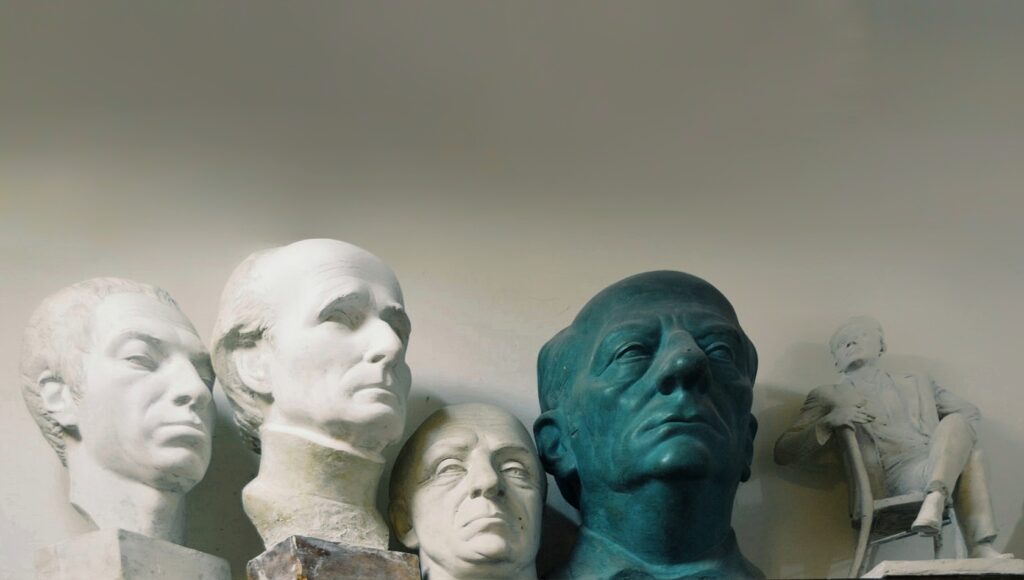

Photo from the sculptor’s workshop. Series of works “Search for Truth”

The literature

— You created a monument to Bulgakov and a bas-relief to Pasternak. Share your attitude towards them?

— Of course, I adore both of them. In addition to wonderful creativity, both Pasternak and Mikhail Afanasyevich had amazing decency. From my understanding, these were high-class people.

Something from Pasternak and Bulgakov is always on my table. During breaks between work, I can re-read something.

— What favorite things could you highlight from Pasternak’s works?

— I love Zhivago very much, as soon as it appeared, I read it with rapture: literally with a sigh. In Soviet times, for some reason many people did not like him. I can’t understand why I didn’t like it? It’s a phenomenal thing.

I also like Pasternak’s poem “Sea Mutiny”; it was written absolutely brilliantly. This poem is very beautiful in form and at the same time very human. I still re-read it avidly. Parsnips are my weakness.

Parsnips are my weakness.

— And from Bulgakov?

— If we talk about Bulgakov, I know that there are people who only like The White Guard. I like it too, but besides it, there is “The Master and Margarita”, “Fatal Eggs” and “Heart of a Dog”.

Moreover, I like absolutely everything from Bulgakov, I can’t single out anything. He had such a successful writer’s vision that he could not write poorly or unsuccessfully. He wrote all his works well. It was given to a man that he was a genius.

— What literature would you recommend reading?

— I would recommend John Maxwell Coetzee – an amazing phenomenon of the twentieth century. He is a South African writer and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. His book “Waiting for the Barbarians” expresses a very deep understanding of time, and indeed of humanity in general. This is a colossal book that amazed me at the time. I also recommend his novel “Dishonor,” which raises the question of human decency, specifically male and female, as well as human relationships.

Besides them, I advise you to read Kawabata, he is also a Nobel laureate and one of the most brilliant writers of the 20th century.

Values

— How do you feel about the vicissitudes of fate? For example, you failed to become an artist, as you wanted as a child, but in the end you turned out to be a great sculptor.

— Life offers such twists and turns that sometimes it takes your breath away. In my opinion, surprise and unpredictability are the most interesting things in life. When everything is smooth and seemingly going as it should, be afraid that something unexpected will happen.

Chance plays a huge role in life. For me, life is full of positive events. In fact, they accidentally took me to the school, they could have kicked me out, but they treated me like a human being. They understood my situation and supported me.

Surprise and unpredictability are the most interesting things in life

— Based on your life experience, tell us what thing is most important in life?

— I believe that health is an indispensable condition for the accumulation and preservation of values in a person. Health includes not only a healthy psyche, but also sensations. In addition, it carries a charge of vivacity. In turn, a sick person brings with him sadness and elegy. Health is the basis for the functioning of mind and body. Moreover, health is the determining condition for life on this planet.

Health is an indispensable condition for the accumulation and preservation of values in a person

— What quality do you value most in people?

— What I value most is decency.” Obviously, everyone appreciates it, but not everyone can be decent. Being decent can be difficult and sometimes costs a lot. The most interesting thing is that at times it seems to a person that decency is worth many losses. However, it only seems that, despite everything, decency is above all.

At times it seems to a person that decency is worth many losses. However, it only seems so.

— What role does the environment play in life?

— Being surrounded by good people won’t hurt anyone, ever.” You give something to people if they come to you, and in return you get something. This happens invisibly. You can’t literally divide I gave this, I’ll take this.

With sincere communication, an amazing penetration of one spirit into another occurs. This is why I value human relationships above all else. If the desired person comes to me, I will give up any work, because I want to communicate with him. In my opinion, there is nothing higher than ordinary human communication, except perhaps love. And love is in everything.

There is nothing higher than ordinary human communication, except perhaps love.

— What would you wish to the younger generation?

— I can’t wish anything specifically for an entire generation, because each person is individual. There are no general rules, especially in art. Everyone searches in their own way and, of course, makes mistakes and stumbles while looking for their truth.

My only wish: to take your work very seriously and carefully. You need to truly understand the meaning of what you are doing, as well as why and how.

There are no general rules, especially in art.

Worked on the material

Yaroslav Karpenko

Editor in Chief

Yana Sychova

Editor